https://www.pazofineart.com/news/5-mark-dagley-recent-museum-acquisition-thesmithsonian-american-artmuseum/

All these strange black crystals lost in the night

the fallen fragments of worlds far, of worlds massive, of worlds far, far away.

There are monstrous ones like corpses of the drowned.

Some go under the moon, along the tides.

There are soft and fine ones like diseases.

There are some velvety and poisonous.

The still dreams. Deserted, immense, lunar.

To the nostalgic grasslands that cradle

and the supple lilac dreams that cling, the ecstasy.

The warm virgins go to the terraces

and the people of the great spheres, tall towards the golden domes,

(always that great dark weight in the sky)

love the ultramarine vegetation love the ultramarine vegetation.

Râaaaaaaaaaaaaga blancâ

The dusty velvet orchestras

watch the strange parade of pierrot’s of camellia below the closed balcony.

Silent fireworks shoot and big diaphanous fish

love the strange black crystals lost in the night,

the complex and decadent flowers loaded with the East,

and the black bouquets in the passionate souls.

Nostalgia of white of white – Algiers at midday – of white of white.

The fresh wood of lilac sins and the spirals the spirals.

There are monstrous and mushy ones, corpses of the drowned.

The hot vines and the warm herbs to the arid nomad.

Others to groups – masses of ivory sheep on the purple hills.

Nostalgia of white of white nostalgia of white

The golden cities far from the minarets the golden sky

travels towards the great still machines on the day of celebration.

(always that great dark weight in the sky)

J.Evola

1920

The plastic narration found in this work from 1994 by George Condo represents a reassertion of a type of compositional structure not found since the late works of Cézanne. Like the French master, and his concern with the structuring of advances made by the more formal impressionists, for example, the de-materialization of subject matter and broken surface tension, Condo reformulates and codifies similar concerns, a type of metaphysical space that one is allowed to access, a place of possible dramatic interpretation similarly found in the work of De’Chirico, Magritte and more recently Guston.

Just as Cézanne’s bathers push space around in tightly knit compositional formats, Condo, in the painting “Lamentation of the Drinker,” allows a grouping of faceless humanoid’s to control and manipulate the residual of geometric and architectural space, while acting out odd histrionic episodes.

Approximately thirty figures occupy this canvas where great tragedy has just taken place, or is about to. The size of the canvas (65 x 81 inches) and the overall composition used represents the format of an eyeball shaped oval. This cycloptic orifice stares out toward the viewer. Dead center, figuratively and literally is the main group of figures witnessing the last (?) moments of “The Drinker.”

Imaginatively thought out, these groups of figures, three “beings”: hovering in space, seven others in severe panic and dressed in black observe or are reacting to the unfolding drama. Unlike Christian exegesis, where Christ, descending from the cross, his mother weeping uncontrollably or even losing consciousness is the main focus of meditation, Condo’s lamentation is a situation suspended between certainty and doubt, where many possibly scenarios could happen. Unless Condo’s main protagonist is experiencing rigor mortis (his arm being outstretched), or dead drunk, he could be alive. A strange group of robed figures look on in wonder and disbelief, others gesture in misunderstanding. If this work is not seen as an elaborately concealed study of certainty and doubt, or the ambiguous nature of perception and belief itself, how else can we decipher the gestures, groupings and interaction between these faceless figures?

Kenneth Rexroth, in a short essay about the artist Morris Graves mentions “deliberate formal mysteriousness…analogous to that found in primitive cult objects,” there is much of that found in this painting, a visually complex riddle. It could be seen as a strange cinematic reflection projected on our memory, always needing to be re-deciphered, its meaning re-established. Therefore, it should not be so strange that the figures that occupy Condo’s “Lamination of the Drinker” have no distinguishing facial features.

Like Cézanne’s bathers they exist within themselves, purely in the space of painting.

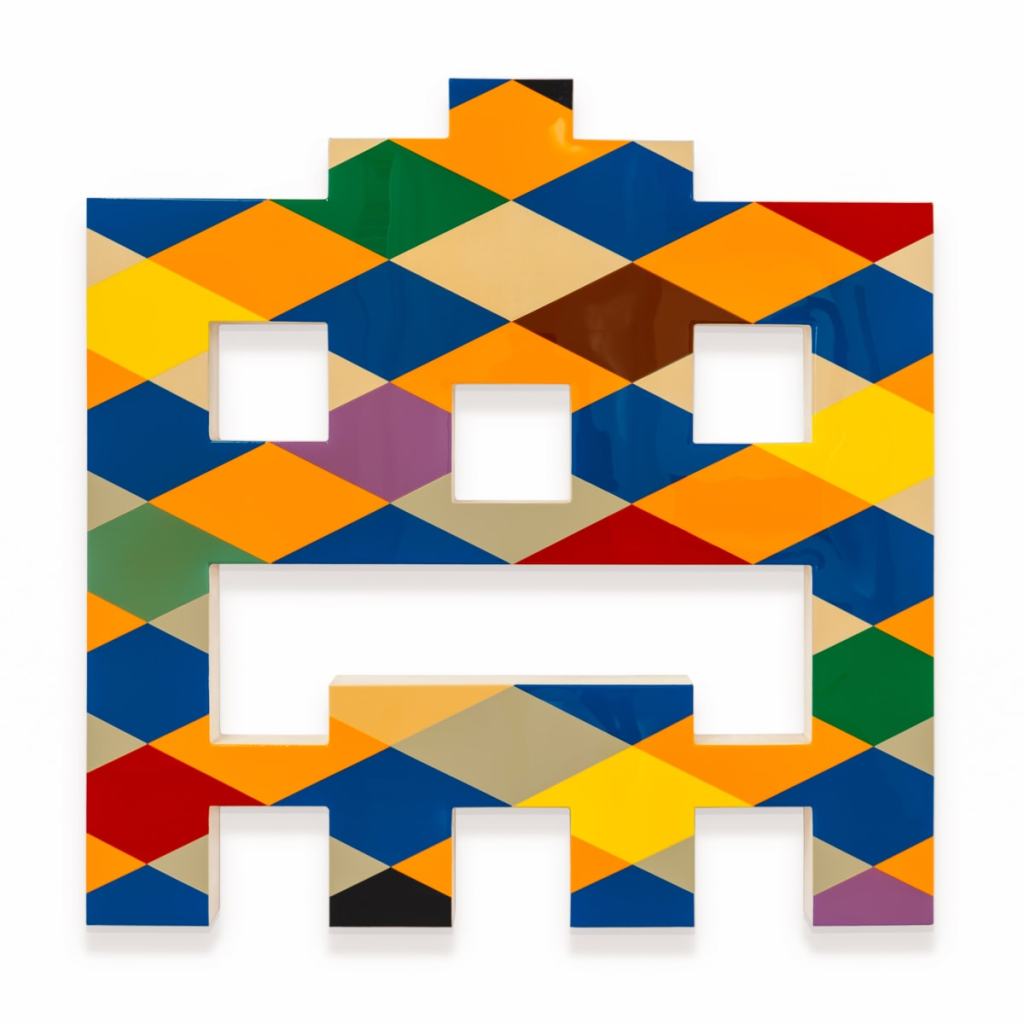

Mark Dagley

1997

Catalog for the Mark Dagley exhibition at the David Richard Gallery, NYC. Perfect bound, 8×10 inches, 60 pages, 40 color plates. Catalog essays by Stephen Maine and Dr. Jan Andres. Available: https://www.amazon.com/dp/0981655025/… Audio ~ “Uranus Hill Fantasy” by MSD – Collected Works 1978-2016 http://feedingtuberecords.com/artists…

Mark Dagley – Bhopal with Satellite, 1986, 80 x 96 inches, Peter und Irene Ludwig Stiftung

Dear artists, estates and gallerists,

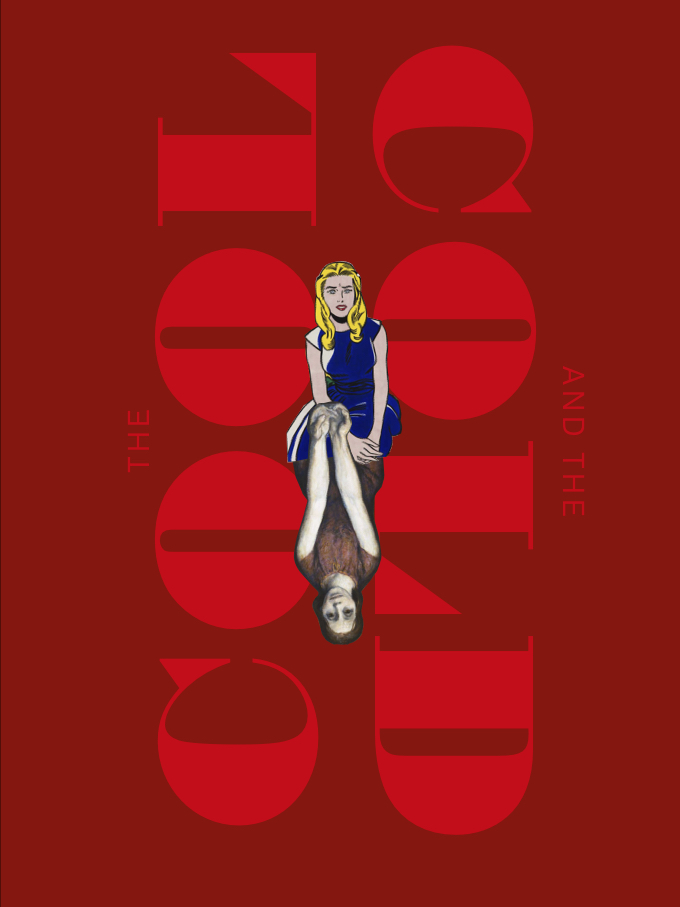

Unfortunately due to the Corona-crisis we are forced to postpone the exhibition “The Cool and the Cold“ at Gropius Bau Berlin to spring 2021. The opening was formerly scheduled for April 24th 2020, setting up was planned to begin today.

The project will now take place September 17, 2021 to January 9, 2022.

We will keep you updated as soon as we know the details. Luckily the catalogue will appear as planned already this spring. It is published by Walther Koenig and as soon as it comes out, we will inform you and send you the book. It will be published in three languages, Russian, German and English, which was kind of an effort to organise but makes us at least very happy now.

I hope very much that you are all well, and that we see each other – safe and sound – in one year in Berlin.

All the best,

Dr. Brigitte Franzen

Vorständin / Chairwoman

Peter und Irene Ludwig Stiftung

Peter and Irene Ludwig Foundation

Eupener Straße 281

52076 Aachen

www.ludwigstiftung.de

Gropius Bau

Press release from 3 March 2020

Running from 25 April to 6 September 2020

In 1989 the Wall came down and in 2020 Germany will celebrate the 30th anniversary of the reunification of East and West. The Gropius Bau takes this occasion to present a comprehensive exhibition drawn to reflect the dialogue and competition between East and West from an art historical perspective, uniting masterpieces from the two global centres of political power that emerged during the Cold War. Peter and Irene Ludwig were among the first collectors worldwide to collect US and Soviet art in parallel. Their extensive collection allows for a critical comparison of works from both sides of the East-West conflict. The exhibition presents a drawn of works from the holdings of the Ludwig Collection from six international museums.

Titled The Cool and the Cold. Painting from the USA and USSR 1960–1990. Ludwig Collection, the exhibition brings together around 125 works by 80 artists, including Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Ilja Kabakov, Erik Bulatov, Jo Baer, Lee Lozano, Jackson Pollock, Helen Frankenthaler, Viktor Pivovarov, Natalja Nesterova and Ivan Čujkov. Installed in 12 gallery spaces in the Gropius Bau’s east wing – with a view of the remains of the Wall as well as the Topography of Terror memorial – the juxtaposition of works reveals the continuities and oppositions between artistic modes of thinking and working. The exhibition examines artists’ reactions to the political and aesthetic questions of their time and how notions of individual and societal freedom were negotiated during the Cold War. In the tensions between competing styles, isms and schools of thought over a three-decade period, art becomes legible as an expression of and commentary on ideologies.

Brigitte Franzen, co-curator of the exhibition and director of the Peter and Irene Ludwig Foundation, on the exhibition: “Peter and Irene Ludwig were among the first collectors worldwide whose collecting activity was truly global. They were always up-to-date. As a foundation, this has left us with an immense treasure – and a unique and complex collection of holdings from which global contemporary history can be read and understood today. The long tradition of the Russian avant-garde and the groundbreaking emergence of American Pop Art are two focal points of the collection. Less well-known, however, is that the Ludwigs also intensively collected the art of the Soviet Union and the USA after the Second World War through the 1990s. This allows for a comparison that reveals the continuities, contradictions, supposed oppositions and historical reference points between both systems in the field of painting. Made evident will be the ideologies that were opposed to each other, or even clashed, which forces were at work and how the Iron Curtain worked in art.”

Stephanie Rosenthal, director of the Gropius Bau: “The Gropius Bau exhibition programme reflects the building and its specific location along the former border between East and West Berlin. The reopening of the main entrance in its original location was only possible after the fall of the Wall; remnants of the Berlin Wall can still be seen from the gallery spaces. The examining of borders and their demarcation therefore runs consistently throughout our programme, emphasized in various ways. In the year marking the 30th anniversary of German reunification, we are particularly delighted to present an exhibition that offers viewers a heretofore unrivalled comparison of works from both centres of Cold War political power. The Cool and the Cold not only brings together artistic perspectives from East and West, but also shows previously unknown works alongside famous masterpieces by Roy Lichtenstein, Jackson Pollock or Andy Warhol.”

The exhibition is curated by Benjamin Dodenhoff and Brigitte Franzen, director of the Peter and Irene Ludwig Foundation. Organised in collaboration with the Peter and Irene Ludwig Foundation.

An exhibition catalogue will be published by Walther König featuring contributions by Boris Groys, Brigitte Franzen and others.

The Black Stack

When Mark Dagley arrived in New York City on the cusp of the Eighties, a social transformation was underway. Economic change in the United States had been foreseen by Daniel Bell as bringing passage to a ‘postindustrial’ era, where the remote management of electronic information and creative agency would come to supplant the production of actual things.

In the artworld, painting was assumed dead, its relevance having faced challenges wrought by dubious critical fortunes and promising new media. Yet the improbable figures Dagley began fabricating soon after his start downtown were prescient, and of a time later recounted as when everything cracked open, with much happening since an elaboration of that freed by the breach.

By the end of the decade, following Bell’s assertion, the realm of analytical finance had become a massive space. It was built out of scratch, designed to facilitate ease of relegation and speed of transfer. Exchange-traded derivatives, collateralized loan obligations, credit default swaps, options on indices, mortgage-backed securities, and other concocted instruments were devised to orchestrate flows which mere convention couldn’t conduct. As risk increased, debt expunged the past and precluded the imagination of a future. Its tally constituted a foundational claim on which enterprise rested. Hypothetical imperatives were disregarded in pursuit of leveraged prerogatives.

With infinite growth an intrinsic paradox, this was, and still is, an untenable long-term gambit. It’s also something to keep in mind when facing the purported end of history, a vexed condition of fractured deferral noted as ‘hauntological’. Mark Dagley’s work mirrors this spirit in its restless manufacture and tactful movement, but more precisely it does so as an analogue of memory, uniquely struck in real time.

And / Or “ – – ”

It would be a mistake to call the devices Mark Dagley has fashioned something they aren’t. How they appear may not be what they are. Each stratagem, intended to disclose a particular mood, warrants recognition of the purpose and ideation gone into it, the attitude and care the effort of its construction entails. Similarities to estimable precedents may cease there. Nonetheless, what Dagley does is interesting. Using the most matter-of-fact means, he drafts a layered diagram of symbol, icon, and index brought forth all as one, one as all, and all at once. This is a radical activity, fixing structure as its cynosure.

When abstraction is considered less as a term of positive value, more as one signifier among many, and prone to scrutiny as a contradiction which models economic goals, differential pressure is brought to bear upon how art is shaped. For instance, is it possible to address the proposition of Google as an object, or as a picture, with meaning communicated through the coupling of medium and form? Conversely, is Google but an idea? How would questions like these be answered? How would the answers look? Digitalization makes representation dispensable above the support of its logic and below the stretch of its surface. In this respect, what you see isn’t what you see. Mark Dagley’s work alludes to this binary order, without being of it as such.

Query By Example

Technical processes never actually banish gesture or intuition. Instead, computation imbues tactile characters with fresh clarity. In its most profound exposition, Mark Dagley’s work resists programmed limits, where output is nominally grasped as metaphoric rendering. In turn, the metonymic displacement initiated by software, which is usually bundled as a written service enabling visualization, access, and delivery, produces a subject in excess of itself. In refuting the status of common resource, this new subject migrates to the trans- disciplinary field of cybernetics, which is likely the true refuge of the avant-garde. Perspective and resolution become factors of quality, if not ethics.

Accordingly, an object that’s not an object isn’t nothing. As Jean Baudrillard noted, it’s the pure object, the object that is none, which doesn’t cease to beset us with its immanence. The apprehension of wood, cotton, brass, copper, enamel, cardboard, and resin, which are materials of commerce and also Dagley’s own, hazards the predicament of viewer and viewed bound in myopic obsession with one another. The subject mistakes the profile of the object for the object itself. In turn, the profile registers the trace of a fallacy, the image of a subject self-satisfied with its own reflection.

Artworks per se aren’t abstract. Mark Dagley’s certainly aren’t. If there’s something to be said here, it’s that.

Mike Zahn

February 12, 2018 Boerum Hill, Brooklyn

Originally posted at https://henrimag.com/?p=9730

Credit Suisse Collection

Credit Suisse Collection

Basel

Summer 2017

Musée des beaux-arts de La Chaux-de-Fonds.